- Home

- Dyhouse, Carol

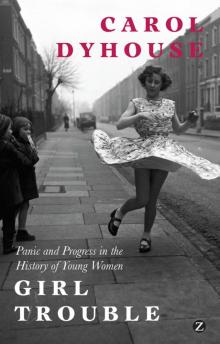

Girl Trouble

Girl Trouble Read online

About the author

Carol Dyhouse is a social historian and currently a research professor of history at the University of Sussex. Her most recent book, Glamour: Women, History, Feminism, was published by Zed Books in 2010. Longer-term, her research has focused on gender, education and the pattern of women’s lives in nineteenth- and twentieth-century Britain. Her books include Girls Growing Up in Late Victorian and Edwardian England; Feminism and the Family in England, 1890–1939; No Distinction of Sex? Women in British Universities, 1870–1939; and Students: A Gendered History.

GIRL TROUBLE

PANIC AND PROGRESS IN THE HISTORY OF YOUNG WOMEN

Carol Dyhouse

Zed Books

LONDON | NEW YORK

Girl trouble: panic and progress in the history of young women was first published in 2013 by Zed Books Ltd, 7 Cynthia Street, London N1 9JF, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA

www.zedbooks.co.uk

Copyright © Carol Dyhouse 2013

The right of Carol Dyhouse to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

Set in Monotype Plantin and ffKievit by Ewan Smith, London NW5

Index: [email protected]

Cover design: www.kikamiller.com

Cover photograph © Bert Hardy/Getty Images

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Zed Books Ltd.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data available

ISBN 978 1 78032 556 9

CONTENTS

Illustrations

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 White slavery and the seduction of innocents

2 Unwomanly types: New Women, revolting daughters and rebel girls

3 Brazen flappers, bright young things and ‘Miss Modern’

4 Good-time girls, baby dolls and teenage brides

5 Coming of age in the 1960s: beat girls and dolly birds

6 Taking liberties: panic over permissiveness and women’s liberation

7 Body anxieties, depressives, ladettes and living dolls: what happened to girl power?

8 Looking back

Notes

Sources and select bibliography

Index

ILLUSTRATIONS

1.1 Innocent victim of the white slave trade

1.2 The white slaver disguised as a helpful gentleman approaching an unwary young lady

1.3 May Day at Whitelands College

1.4 May Queen in 1911

2.1 Girl suffragette in Trafalgar Square

3.1 The modern girl discussed in Girl’s Favourite

3.2 Pyjama-clad, cigarette-smoking flapper

3.3 Amy Johnson, aviator

3.4 Girls inspired by Amy Johnson

3.5 Factory girls in Walthamstow modelling carnival hats

3.6 ‘Miss Modern’ resplendent in her cutting-edge swimsuit

4.1 Scene from the controversial film Good Time Girl

4.2 Betty Burden helping her mother with the weekly wash

4.3 Young women working in a clothing factory in Leicester

4.4 Schoolgirls show off their cake-making skills

5.1 Poster advertising the film Beat Girl

5.2 Mandy Rice-Davies

5.3 Trendy teenagers at Brad’s Club, London

5.4 The lure of the jukebox

5.5 Beatles fans outside Buckingham Palace

5.6 Katharine Whitehorn photographed for Picture Post alone in a bedsit

5.7 Dolly birds on the King’s Road

6.1 A young Marianne Faithfull looking innocent

7.1 Rotherham punk Julie Longden and friends pose in a photo-booth

8.1 Girls leaping with joy at their exam successes

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I owe thanks to the many librarians and archivists who have facilitated the research on which this book is based. In particular, I would like to record my appreciation of the helpfulness of staff in the British Library (both at St Pancras and at the newspaper division in Colindale), in the Library of the University of Sussex, and in the National Archives. Thanks also to staff at the County Record Offices in Warwickshire and East Sussex. Archivists at the Salvation Army Heritage Centre, the Women’s Library, and Tower Hamlets Local History Library guided me towards some rich material. At Whitelands College, now part of the University of Roehampton, Gilly King was exceptionally hospitable and enthusiastic in explaining Ruskin’s legacy and the history of the college.

The team at Zed Books has once again turned the publication process into a pleasure. My thanks to all of them. I am grateful to Pat Harper for her meticulous copy-editing and to Ewan Smith for his skills in production. Warm thanks, also, to Maggie Hanbury and her colleagues at the Hanbury Agency.

For permission to reproduce images I am indebted to the British Library, Whitelands College at the University of Roehampton, Getty Images, Tom Phillips, Tony Beesley and Julie Longden, Gabriel Carnévalé-Mauzan, PA Wire, and IPC+Syndication. Every effort has been made to trace and to acknowledge copyright holders of the illustrations reproduced in this book. The author and publisher apologise for any unintended errors or omissions in this respect. If brought to their attention, any such errors will be corrected in future editions.

This book is the product of research that I have carried out over a long period of time. It isn’t an easy matter to compile a list of all the people who have helped me to bring the work into shape over the years, so I have to be selective, and to hope that anyone who feels left out will forgive me. As ever, my fondest debt is to my immediate family: to Nick and to our daughters Alex and Eugénie von Tunzelmann. Their positive thinking, their critical intelligence, and their encouragement in the face of my tendency to quail have been both heartening and indispensable. Then there are friends whose generosity and support I value immensely: most of these are scholarly types and they have always been ready to discuss ideas with me. My thanks to Jenny Shaw, Marcia Pointon, Claire Langhamer, Lucy Robinson, Pat Thane, Hester Barron, Naomi Tadmor, Selina Todd, Lesley Hall, Penny Summerfield, June Purvis, Penny Tinkler, Hera Cooke, Stephanie Spencer, Lucy Bland, Joyce Goodman, Ruth Watts, Sally Alexander, Anna Davin, Jane Martin, Ulrike Meinhof and Amanda Vickery. Thanks also to Ros McLintock and Monica Collingham, both of whose friendship and support go back for many years. Monica’s enthusiasm for local history in Tower Hamlets led me to the riches of the Edith Ramsay Collection. Colleagues at the universities of Sussex and Brighton continue to be important in so many ways: as well as those already mentioned, I have profited from discussions with, and encouragement from, Ian Gazeley, Jim Livesey, Paul Betts, James Thomson, Vinita Damodaran, Saul Dubow, Beryl Williams, Ben Jones, Becca Searle, Lucy Noakes, Maurice Howard, Vincent Quinn, Sian Edwards, Lesley Whitworth, Jill Kirby, Sian Edwards and Chris Warne. As well as making insightful comments, Owen Emmerson reminded me about the depiction of white slavery in Thoroughly Modern Millie. Thanks to Miriam David, Gaby Weiner and Alexandra Allan for helping to keep me in touch with recent work in gender and education. Andy Smith was generous in lending some hard-to-get books. James Thomson put up with me in a shared office and helped me to negotiate in French with copyright holders. I must also thank the staff in the University of Sussex’s IT Centre, without whose support I simply could not have managed. They were unfailingly brilliant when I panicked over technical stuff. So, thanks to Paul Allpress, and particularly to Alex Havell and Claire Wallace, Luke Ingerson, Miles Dymo

tt and Neil Forshaw. Gill Powell patiently explained the tricky business of how to get the bibliography to follow the endnotes.

INTRODUCTION

Are girls better off today than they were at the beginning of the twentieth century? Conditions vary widely across the globe. In parts of the world girls suffer disproportionately from poverty, lack of education, and appalling levels of sexual violence. But there can be no doubt that in some countries, at least, they have more opportunities, more choices and infinitely more personal freedom than ever before. Does this mean that we can afford to be optimistic about the impact of modernity on girls? Have young women emerged as winners rather than losers in modern history?

These are large questions and beg larger ones. This book is more modest in its remit and focuses primarily on Britain, although it is informed by writing and ideas about girlhood from North America, Australia and Europe. Many of the issues and themes which are dealt with will be familiar to readers outside these regions: controversy about whether girls should be seen as the victims or beneficiaries of ‘progress’ have had a very wide currency.

In what ways are girls better off in Britain now than they were in Victorian times? Whereas in the past girls were schooled for home duties and pushed into domestic service, they are now educated along much the same lines as boys. And they do extremely well in education, at both school and university levels. As far as work opportunities go, young women have many more options than their mothers had, and certainly vastly more choice than their grandmothers. Many liberties are taken for granted: political rights, the freedom to move about the city, to drive cars, to operate bank accounts, to enter into contracts, to take out loans and to manage financial affairs. All this would have been unimaginable in the 1890s, and even in the 1950s and 1960s bank managers (then all male) routinely refused to grant young unmarried women the mortgages that would have allowed them to own their own homes. Up until the 1970s, opportunities for sexual self-expression were limited. Girls were generally assumed to be in pursuit of husbands. They were expected to remain chaste before marriage, and anything else – especially unmarried pregnancy – brought social shame and a prospect of doom. Today, most girls in Britain have much more control over their bodies and their sexuality.

This is not, by any means, to assert that everything in the garden is rosy. Young women today face many problems. Some of these are new, and some are depressingly familiar. There are still ‘double standards’ of sexual morality, for instance. Boys have more licence, and they get away with much more. Young women suffer more than men do from bullying, and from sexual violence. And girls are too often expected to be perfect in every way: at school, in work and behaviour, and in the way they look. Subjected to such pressures, they can turn their anger and a sense of powerlessness, or lack of control inwards, resulting in eating disorders and depression.

A great deal of contemporary writing on girlhood has been gloomy in tone. Young women are represented as the victims of all manner of social trends: of capitalism, of consumerism, of body obsessions, of ‘sexualisation’ and pornography. Girls themselves come under attack for behaving badly: as alcohol-swigging ‘ladettes’ or as narcissistic ‘living dolls’. They may be represented as defenceless innocents or as brainless Barbie-doll impersonators, floating in a fluffy cloud of self-obsession, sparkly pink, and fake tan. Several academic writers have argued that the language of ‘girl power’, ‘empowerment’ and ‘choice’, often used in accounts of the recent history of girls, has served as a smokescreen, obscuring deep-seated inequalities and oppression. Scholars such as Angela McRobbie, Jessica Ringrose, Anita Harris and Marnina Gonick, for instance, have suggested that a liberal discourse of ‘freedom’ and ‘opportunity’ can disguise the fact that realistically, there are far too many girls in even the developed world who enjoy very little of either.1 There is undoubtedly some truth in this, and the economic uncertainties and widening social divisions of the twenty-first century so far give little cause for complacency. The improvements in young women’s lives which became noticeable in Britain, particularly after the 1970s, can never be taken for granted: it isn’t difficult to find evidence of the ‘backlash’ which led so many observers to speak of ‘post-feminism’.

This book brings together work I have done throughout a longish academic career. This began in the 1970s, when I first became interested in the ways in which, historically, female education functioned as a battlefield for different constituencies, all convinced that they knew what was best for girls. In Britain, Victorian feminists objected to an education designed to groom girls for the marriage market. Their opponents held that too much intellectualism unsexed young women: at best, it turned them into desiccated spinster types; sometimes, it was claimed, it literally shrivelled up their breasts and ovaries, rendering these women infertile.

If social anxieties surfaced around women’s struggle for a decent education in the late nineteenth century, in Britain these anxieties paled in comparison with the agitation generated by feminist demands for the vote in the years 1900–1914. The conflicts of this period can realistically be described as a ‘sex war’, in which both sides showed intransigence and extreme reactions. This war between the sexes escalated around the government’s practice of force-feeding suffragettes in prison in 1913. For many women, force-feeding was experienced as torture, or a form of rape.2 The early twentieth-century panic over ‘white slavery’, and particularly the alleged kidnapping and trafficking of young girls on city streets in Britain and America, reached its height in precisely the same years. This moral panic reflected the fraught situation of antipathy between the sexes. It brought together an unlikely combination of political groups: evangelicals, social purity workers, feminists and staunch opponents of women’s suffrage. Campaigners focused obsessively on the idea of innocent young girls as the defenceless victims of predatory male lust. For some, these stories of white slavery exuded a distinctly erotic appeal.

The book begins with these horror stories about girls being kidnapped on the streets of London. It then moves back in time to trace the ways in which a growth of feminine self-awareness, improvements in education, and a growing political consciousness made their impact upon young women before the First World War. The troubling of social certainties about gender continued through and after the war, as the ‘modern girl’ established herself on the scene. ‘Brazen flappers’ horrified conservatives by blowing cigarette smoke in the face of Victorian ideas of feminine constraint and decorum. Young working-class women’s determination to live more fully and their ambitions for a better life led them to shun domestic service in favour of new opportunities in shops, factories and offices. This created problems for the servant-keeping middle classes, who whinged incessantly about young girls getting above themselves, and showing too worldly an interest in cheap cosmetics and fur coats. Cinema-going was often blamed for this, in the sense of turning girls’ heads. But a shortage of marriageable young men in the aftermath of war also fostered an independent outlook in many single girls. Whether they liked it or not, these young women often had no one else to depend upon.

Respectable society had no answers to many of the predicaments faced by young women, especially those forced to strike out on their own. The Second World War, like its predecessor, proved a catalyst of social change. Chapter 4 shows how, for many people in Britain, the pace of change was itself threatening. Anxieties about young women surfaced in alarm over ‘good-time girls’, seen as predatory, lusting after foreign men or on the lookout for no one but themselves. There were rumours of these girls batting their eyelids at American servicemen and risking their virtue for nylon stockings. Such concerns carried over into the post-war world. The 1950s was a decade of extraordinary contradictions. The coronation of the young Elizabeth II brought a wave of nostalgia for an idealised past, in which tradition and hierarchy were assumed to have buttressed the British. Dutiful upper-middle-class girls queued to become debutantes, grooming, learning to curtsey, and trussing themselves up

for the marriage market. But new conditions were intruding fast, often loudly signalled by American-style consumerism, film and popular music. There was concern lest daughters be seduced by ‘crooners’, or go after bad boys in leather with slicked hair like Elvis Presley. Then there were Teddy girls, beat girls and Mods.

Harassed fathers were disturbed by the idea of daughters hanging about jukeboxes in coffee bars, or coming across undesirable types in dark and smoky jazz cellars. Would these daughters prove wayward, swerving out of control? Runaway marriages or unmarried motherhood would bring shame on a family’s good name. Chapter 5 focuses on the 1960s, unsettled by the Profumo scandal and the teenage revolution.3 Girls were seen to be behaving in ways which challenged traditional authority and standards of propriety. Increasingly well-educated, they were more often answering back, and threatening to leave – if not actually leaving – home. Chapter 6 explores the ways in which controversies over the ‘permissive society’ were bound up with unease about changing gender roles, and further, stemmed from fears that girls were behaving precociously and promiscuously, without regard for the consequences. There was a minor moral panic about unmarried, teenage motherhood, but those who fretted most about this were often equally uneasy about young women getting access to contraceptives without their parents’ consent.

One of the lasting legacies of the teenage revolution of the 1960s in Britain was the redefinition of adulthood: after the Family Law Reform Act of 1969, young people were regarded as ‘coming of age’ at eighteen rather than at twenty-one. This defused what had often been an explosive situation in both families and educational institutions. Throughout the 1960s, young people of both sexes had regularly challenged what they had increasingly come to see as unwarranted and ‘paternalistic’ interference in their private lives. After 1969, students in colleges and universities gained a great deal of personal freedom: the authorities were no longer required to act in loco parentis towards them, because eighteen-year-olds were no longer considered ‘infants’ or ‘minors’. Young people over the age of eighteen could henceforward marry without the consent of their parents, should they wish to do so. Those who worked to bring about this reduction in the age of majority had been much influenced by the fact that young people – especially women – were marrying at younger ages than in the past. However, contrary to all expectations, the numbers of teenage brides sharply diminished in the 1970s.

Girl Trouble

Girl Trouble